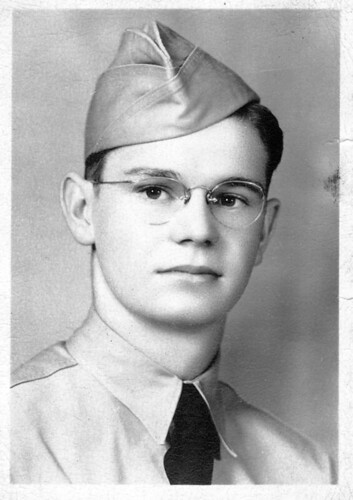

My father, James Nelson Cummins, enlisted in 1943 at age 18. When the troop hit the beaches in France, he was a PFC (private first class) in Ft. Sill, OK at The Artillery School, assigned to a "flash-ranging" platoon (forward observers—FO). Back to Georgia, promoted to buck sergeant and headed out that September on what was once the luxury liner USS Manhattan, stripped down to hold 20, 000 troops. They crossed the Atlantic without escort (the story was that they were so fast that no U-boats could find them) and landed at Liverpool. Eventually they crossed the English Channel and landed on Omaha Beach. There was all kinds of wreckage there from 3 months earlier.

His battalion found out that their equipment has been on a different ship, which had been sunk, so they pitched tents in Normandy and waited for replacement equipment. When it arrived in early December, they headed for Belgium and the front. Almost there they got word of the Bulge fighting and that their sister battalion, 287 FA Ob, had been captured at Malmedy and butchered—which didn't help their morale.

My father writes: “We were not a bunch of heroes. Mostly did counter-battery work—locating German artillery, heavy mortars, rockets and tanks and directing fire on them. Wound up on the Elbe, north of Magdeburg. Crossed the Elbe to finish things off at Berlin; called back to the west bank orders of Ike; sat there and watched from about 30 miles out the fires of Berlin; watched the remnants of the Wehrmacht coming west, flowing south east of the Elbe. Watched the Russians chasing them. Finally, surrender.”

The war wasn’t over for my father, though. Because he had joined the fighting late, he was earmarked for continuing service by going to Japan. He was sent home in July with orders for 30 days leave, then to report to west coast and passage to the Far East. I have often imagined —but can’t possibly—how he felt when they landed in Boston harbor to the cries of newsboys hawking papers with headlines "Second Atom Bomb Dropped on Japan!" I imagine all those days crossing the ocean, knowing that, though he was done battling in one continent, he must barely take a breath and then head off to another. And then, to have the atom bombs be his saving grace. It has always been hard for me to read Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes, because on one hand I am horrified and terribly sad, but on the other hand….my father.

In 1947 my father finished his degree at Cornell University on the GI Bill. That semester he and some friends decided that Stalin was “getting really nasty,” so they enlisted in the Army Reserve. After graduation he headed back to Southern Illinois and joined his Dad on the farm, got married, and had my oldest brother in July of 1950. Two weeks later he received orders to report to Ft. Lewis, Washington, for immediate shipping to 16th Field Artillery in Korea. It was nearly a year before he went to Korea, having received a commission in the Quartermaster Corps that first took him to Ft. Lee, Virginia. But ultimately he landed in Pusan where he was shipped trainloads of groceries to troops in the north and promoted to 1st Lt. He was offered a offered captaincy but instead came home to help his Dad on the farm in 1952.

Back in Illinois he continued in active Army Reserves, usually as infantry officer. Changed to Medical Service Corps and had three more sons. In middle of his doctoral studies at Southern Illinois University, he received ultimatum from Army -- either take command of a reserve Ambulance Company at Belleville (60 miles away) or retire. So he reluctantly retired about 1965. My father writes: “I could be negative about military service. I'm not. The Army made a man of me; gave me an education through GI Bill; gave me a strong sense of having served my country.”

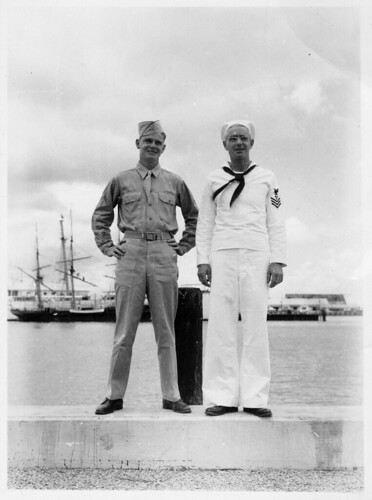

My Granddad, Nelson Andrews Cummins, went into navy in 1942, an apprentice seaman at age 41. He went to Great Lakes for his boot camp; aptitude tests pointed him toward mechanical. Stayed there for motor mechanics school, then went to advanced diesel engine school. He was promoted to MMM 1st class and assigned to a destroyer escort (DE) -- essentially a small destroyer, but powered with huge diesel engines rather than steam turbines (standard on destroyers, DD). He was promoted to Chief MMM, in charge of the engine room under the Engineering Officer. His ship went to far Pacific as support for the Okinawa landing. On the second day of the invasion, Granddad was ordered to go ashore where he had charge of diesel-powered generators that supported the fleet admiral's radio commo. His DE was sunk by kamikaze. He retired as a Chief Petty Officer and returned to his orchards in Dix, Illinois.

And so my father and his father and thousands of other fathers returned home after wars, and thousands did not. My father is 81 years old now, and my Granddad died over 30 years ago. And there is this huge part of my father's life that he remembers in all its details: the exquisite taste of hot cocoa made from bars of chocolate shaved into cups while camped above the Elbe, the Jewish clerk from NYC and his "an-coy-vees," card games on the ship, seasickness crossing the English Channel. Missing his first child's first steps and first words. Battling moral conflict. What war takes from and adds to one man's life, we who have not, can never know.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I love comments! Thanks for taking the time to leave one. I have comment moderation on, so your comment will take a little bit to appear.